Strachey's True Report of the Sea Venture

A Modern Translation

A modern translation of the 1609 - 1610 work of William Strachey about the Sea Venture ship wreck, survival on Bermuda Island, and eventual trip to Jamestown.

Shorter Sentences

Decisions needed to be made in constructing this modern paraphrase: shorter sentences are easier to read while longer sentences can be quite elegant. Verbosity was not a fault that Strachey's contemporaries feared to be accused of.For instance, instead of stating "I made the sentences shorter," Strachey would likely have written: "Sentences, you may note if you are pleased to follow the original, are shorter in this newly-framed and modern version undertaken for the benefit of esteemed contemporaries; because it is a phenomenon to be noted by those who study the older examples of literary excellence that sentences of yore were far longer and much less brief."

Modern Language

While using as much of his original as possible, I shortened sentences and, in cases where italics are employed, added or substituted words to make his meaning clear. The "thee's" and "thou's" and "thine" have been changed to "you" and "yours." Unfamiliar words were either changed to a modern equivalent or explained in parenthesis.Other Minor Changes

Dates have been written in modern format (January 1, 1600) but not changed to the modern Gregorian calendar where dates were advanced 10 days.Bolded words indicate information from outside of Strachey's text (either additional information, geographic information, or editor comments.) Bolded information here is comparable to foot notes in a printed text.

In this transliteration we have modernized the spelling of names and places. (For instance, Admiral George Somers is used instead of Strachey's spelling of "Summers.")

Strachey was a literary man with a real love of the ancient classics whom he often referred to while making a point. Since these are generally unfamiliar to modern readers they require significant attention to explain how it is related to our topic. Rather than clarify Strachey's descriptions, such references merely confuse the point. Hence they have been removed.

With these changes, Strachey's narrative is a quick and easy read not requiring the reader to slow down to mentally transliterate the sentences from Elizabethean English to their own language. Instead of enduring an exercise in translation, the modern reader can relive the dramatic events recorded by Strachey's pen as "the clouds gathered thick upon us, and the winds sang and whistled most unusually."

Chapter One

Storm and Shipwreck

To our Dear Excellent Lady;It was late on a Friday night on June 1, 1609 that we left Plymouth, England. Our whole fleet of ships consisted of seven good sailing ships and two smaller pinnaces that were towed by two of the larger ships. From June 2 until July 23 these nine ships sailed in friendly consort, keeping in sight of each other, with passengers waving and calling to those on the other ships. At no time did we lose sight of one another.

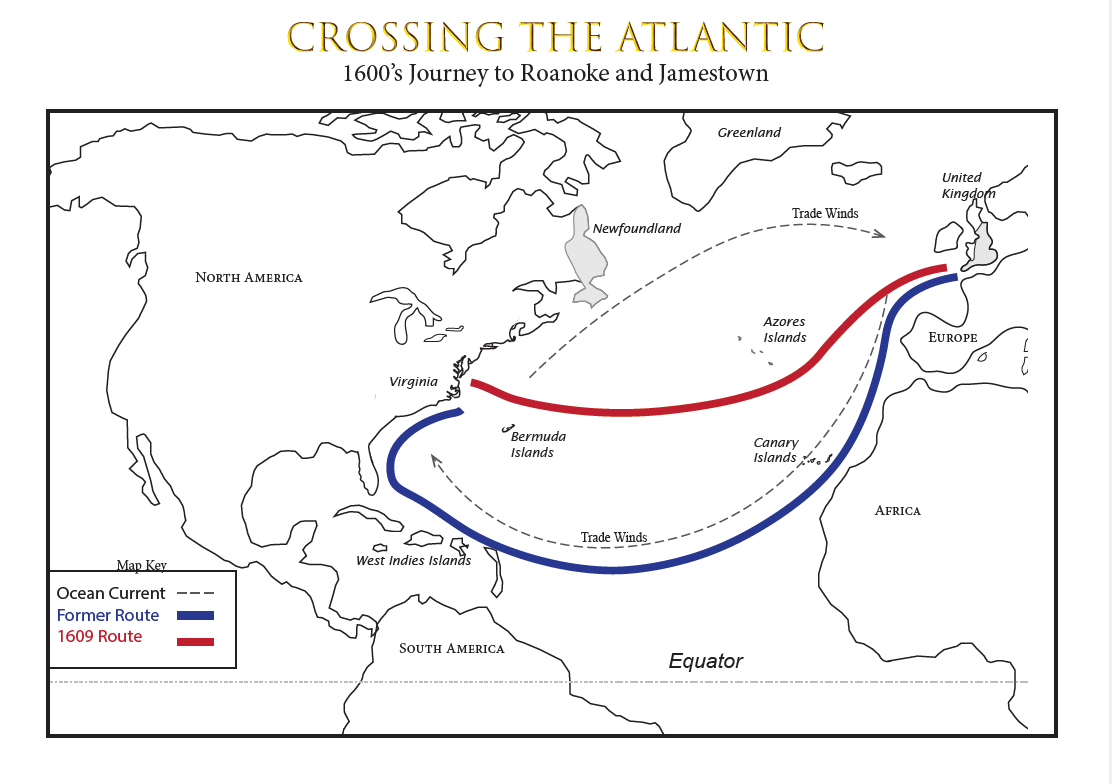

When we sailed to 26 to 27 degrees latitude, just a little past the Canary Islands on the west coast of Africa, we started to head north according to our governor’s instructions. This was a little different course than was ordinarily used with the trade winds to sail to the West Indies. Happily we found the wind in this new course indeed as friendly in the judgment of all the sailors. It was a more direct line.

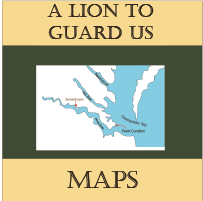

Red route is 1609 route by Argall. The intended route of Sea Venture & fleet would be between the red and blue lines.

The captain of the largest ship, Sea Venture, which I was on, was Captain Christopher Newport. He had made more trips to Virginia than other than captain and he reckoned we were within seven or eight days at the most from the coast of Virginia.

On Monday, July 24 the clouds gathered thick upon us, and the winds sang and whistled most unusually. The Sea Venture had been towing a pinnace behind us, but we had to cast off the ropes to prevent the two ships from wrecking into each other and both sinking. A dreadful and hideous storm began to blow from the northeast. The waves swelled and soared by fits, for many hours, some waves more violent than others. At length the storm beat all light from heaven which was like a hell of black darkness. The horror and fear troubled us all and overmastered our senses with the terrible cries and murmurs of the wind. It distracted our company, most of whom were armed and well-prepared, but all were shaken. For surely, dear noble lady, death comes much more suddenly for those who are sea. But so weak was our hope in the miserable danger we were in. Indeed at no time or place is death incapable of providing comfort as much to those who are at sea.

For twenty-four hours the storm was a great restless tumult that we could not imagine any greater violence. But then it did become more terrible, more constant, fury added to fury, and one storm urging a second storm more outrageous than the first. Our fears increased as we met with these new forces.

Passengers not used to such waves looked at each other with trembling and troubled hearts. Our cries were drowned in the winds, and the winds were drowned in the thunder. Prayers said in the heart might have been heard but those spoken out loud were drowned in the outcries of the officers yelling instructions at the sailors. Nothing heard could give comfort, nothing seen might encourage hope. It is impossible for me to express the miseries.

Our sails were useless, wound up. And if at any time we bore the hullock, (the small sail that guides a ship’s head in a storm six, seven, or even eight men were not enough to hold the whipstaff and the tiller which steer the ship from below deck in the gunner room. Imagine the strength of that storm in which the sea swelled above the clouds and fought the skies above us.

I cannot say that it rained. The waters above us was like whole rivers flooding the air. And here is something else I observed: On land when a storm has poured itself forth in drifts of rain, the wind does not last much longer. But in this storm here the glut of water was no sooner a little emptied but instantly the winds grew louder and more tumultuous and malignant. What shall I say? Winds and seas were as mad as fury and rage could make them.

For my own part, I had been in storms at sea before. Yet all the storms I had ever suffered combined could not compare with this. Every single moment we expected our ship would suddenly split apart or turn over.

But this was not all. An even greater affliction befell us! At the beginning of the storm the ship got a mighty leak. In almost every joint the oakum which fills the gaps between planks had been spit out before we were aware of the leak. This was a casualty more desperate than any other that can occur on sea.

Before we were aware of the leak, the water in the hold of the ship had grown to more than five feet above the ballast (the rocks at the bottom of the ship that keep it afloat.) Now we almost drowned inside the ship even while we sat looking to perish from above. Terror mixed with danger ran through the whole ship, so much fright and amazement. It turned our blood cold. The bravest and most hardy mariner of them all who previously had felt not the slightest bit of sorrow now began to feel sorry for himself when he saw such a pond of water inside our ship. He knew we should sink instantly, so he joined the others if only for saving his own skin, even if he didn’t care to save anyone else.

We had to find the source of the leak to stop the water from coming in. One could see the ship’s master, master’s mate, boatswain, quartermaster, coopers, and carpenters with candles in their hands, creeping along the ribs, carefully inspecting the ship’s sides, searching every corner, and listening in every place, if they could hear the water run. Many weeping leaks were found this way and hastily stopped. But after a length of time the sides of the gunner room were filled with countless pieces of beef. Such priceless food for our journey was used to stuff the gaps between the boards of the vessel to replace the soggy oakum that had come out. We would have no need for food if we could not find the leaks and fill the holes. But it did no good.

Such a leak. We never knew if it was one or many, but this leak which drank in the great sea, hastening our destruction could not be found. We never found it, by any labor, counsel or search. The waters were still rising and the pumps were working to bail out the rising water.

Then the pumps choked. The rising water had caused all the biscuits to float and they in turn clogged the pumps that attempted to rid our vessel of the water. Most likely, then, the leak must have started in the room where the bread was stored Therefore our carpenter went down and ripped up the room. Even then the leak was not found.

I cannot tell Your Ladyship what every person was thinking in this perplexity; but to me this leak appeared as a wound given to men that were already dead. The Lord knows I had no hope in this storm, and it went beyond my will or my reason that we should continue to labor to save our lives. Yet we did. Either because even a few last lingering hours of life are so dear in all mankind or that our Christian knowledge taught us that we owe the rites of nature not to be false to ourselves or to neglect our own preservation. For the most desperate situations among men are matters of no wonder with Him who is the rich fountain of mercy.

On Tuesday morning, Sir Thomas Gates, our appointed Jamestown governor, divided the whole country into three equal groups. There were one hundred and forty men (including passengers and sailors) in addition to thirteen women and children. Each group was assigned to work in one of three parts of the ship: under the forecastle, the waist of the ship, and the bitts (vertical poles) in the fore of the ship. Every man came duly upon his watch for one hour, took the bucket or pump to get rid of the rising water in the ship, and after one hour rested while another worked. The men might be seen to labor for their very life. The wealthy aristocrats and the common laborers both worked, our governor and admiral themselves taking their turns while giving another their one hour to rest. The common laborers stripped off their clothes as naked slaves in a galley ship because it was easier to hold out and to work under the salty sea water which continually leapt between men. They kept their eyes awake and their thoughts and hands working even with tired bodies and wasted spirits for three days and four nights. We were all destitute of any outward comfort and without hope of any deliverance. But each worked diligently to keep the other from drowning, even though one almost drowned while it was his turn to pump the water.

Once, the sea broke upon the poop deck in the stern (back) of the ship and the captain’s quarter deck behind the main mast. From stern to stem the water hit our ship. Like a vast cloud, it filled her brim full from the hatches in the bottom up to the spar deck. This flood of water was so violent as it rushed and carried the helm-man from the helm and wrested the whipstaff out of his hand. In fact, that whipstaff flew so hard from side to side that he could not seize it again but it tossed him from starboard to larboard (from the right side of the ship all the way to the left side) and it was God’s mercy that it did not split him in half. It so beat him from his hold and so bruised him. Another man, hazarding near him by chance, fell upon the whipstaff and by brute strength held it while calling others for help. But we all thought the ship was absolutely lost.

Sir Thomas Gates, our governor, was below the capstan and both by speech and authority motivated every man to continue his labor. The water struck him so he fell on his feet, and all of us about him fell on our faces. All thoughts escaped us except that we were now sinking. For my part, I thought the ship was already at the bottom of the sea. Gates later told me his only thought was to climb above the hatches and die under the open sky in the company of his old friends. The ship itself was so stunned by this deluge of water that had dropped on us from our of the sky that it stopped in its full pace and went forward no more as though she had been caught in a net. At this time she had been making nine or ten leagues in a watch (27 to 30 miles in four hours.)

Even after that tremendous burst of water had fallen out of the sky onto our ship, not a single person, not a passenger or sailor, gentleman or laborer, but they began to stir and work hard to make sure his fellow worker could be relieved. And even those who had never done a good hour’s work before in their life found the motivation for their mind to help their body and were able to toil with the best for the next forty-eight hours.

During all this time, the sky looked so black that it was not possible to see the elevation of the North Star or any star by night, nor any sunbeam by day. But on Thursday night (July 27)an amazing things happened.

It was our Admiral Sir George Somers who was on the watch and he saw an apparition of a little round light like a faint star, trembling and streaming along with a sparkling blaze halfway up the main mast. The light would shoot from one shroud to the next, acting as if it were going to settle upon one of the four shrouds that held the mast up. For half the night this light kept with us, running sometimes along the main yard to the very end and then returning. Admiral Somers called different people to him and showed him the light, and they all observed it with much wonder and carefulness. And all of a sudden towards the morning it disappeared and none knew where it went.

Many seamen were superstitious and conjectured about this sea fire. Nonetheless, it has been known to show up during storms at sea. It has been described by the Greeks, and the Italians, and the Spaniards call it Saint Elmo’s Fire and have a miraculous legend about it. As it was, it didn’t seem it effected our safety or our ruin. If only it could have helped the mariners measure the height so we could tell where we were on the ocean, our amazement might have turned to the reverence. But it did not enlighten us even a little bit to know our way. For now we ran as blindfolded men in a dangerous adventures, sometimes heading north and northeast, then north and northwest. Sometimes our direction varied by two or three points and sometimes by half the compass.

We steered east and southeast as much as we could to keep our vessel upright, which was difficult to do. We unrigged our ship, threw overboard much luggage. Many a trunk and chest was tossed into the water below and I myself suffered a significant loss of my possessions. Many a butt of beer, hogsheds of oil, cider, wine, and vinegar were heaved as well as our cannon on the starboard side. And now, we had to decide to cut down the mainmast to lighten the ship. Our men were so weary and their strength failed them as well as their hearts. All had travailed from Tuesday until Friday morning, day and night, without sleep or food. Because of the leak we had had neither beer nor fresh water, no fire could be lit in the kitchen to make a meal. Our hourly turn at the pump or bucket prevented any from sleeping.

With three pumps continually working we were draining over one hundred tons of water (200,000 pounds) every four hours. So, Madam, from Tuesday noon until Friday noon we bailed and pumped two thousand tons. And yet, as hard as we worked, she bore ten foot deep in the hold on Tuesday night in the second watch. But now, on Friday, the fourth morning, there was nothing more we could do. There was a general determination that the time had come to shut the hatches and commend our souls to God and the ship to the mercy of the sea. Surely that night we would have had to do it and then that night we would have perished.

But see the goodness and sweet introduction of hope by our merciful God given to us: Sir George Somers, when no man dreamed of such happiness, cried “Land!”

Indeed that morning which was already three quarters spent, was a little clearer from the days before. And we saw trees on that land moving with the wind on the shore. Then our governor commanded the helm‑man to bear up. The boatswain checked the depth of water and it was thirteen fathoms. We sailed closer and it was seven fathoms. And finally heaving his lead the third time we were at four fathoms.

By this time the ship had sailed within a mile of the southeast point of the land, where the water was smoother. There was no hope of saving the ship by dropping the anchor so we were forced to run her ashore as near the land as we could. This brought us within three quarters of a mile offshore. By the mercy of God, using our small boats, before night we had brought all our men, women, and children (about one hundred and fifty total) safe onto the island.

Geography and Climate of Bermuda

We found it to be the dangerous and dreaded islands called Bermuda. Let me give Your Ladyship a brief description of these islands before I continue my narration of the shipwreck. These islands are so terrible to all that ever landed on them because of such tempests, thunders, and other fearful objects seen and heard on them that they are commonly called “the Devil’s Islands.” They are feared and avoided by all sea travelers more than any other place in the world. Yet it pleased our merciful God to make this hideous and hated place both the place of our safety and means of our deliverance.Now I hope to deliver the world from a foul mistake about this place when they say it can not be a habitation for men since it is the home of devils and wicked spirits. Instead, we found it to be as habitable and commodious as most countries of the same climate. The largest problem is that the entrance to these islands is very dangerous as they are surrounded by shallow rocks which will tear a ship to pieces. But once one navigates these rocks and reaches the islands themselves, the place is very desirable. If this had been known before, it would have been inhabited before now. Since truth is the daughter of time, men ought not to deny things which they can’t see for themselves.

The Bermudas are a series of small, separated islands, five hundred of them in manner of an archipelago, which is a chain of islands. Now when I say there were five hundred islands, some of them can barely be called islands - they are so small and lie so low in the sea which has crept into and made a passage through the land. They lie in the figure of a croissant within the circuit of six or seven leagues (15 to 19 miles.) Previously it had been written that they were 13 to 14 leagues in length (29 to 32 miles). You can see on the attached map (which has been lost apparently) that from the northwest point to Gates Bay it is no great distance. This map was made by George Somers who coasted around the islands and took great care to be exact and make his draft perfect for all the benefit of either ships in distress or those purposely sailing here.

These islands were written about by Gonzalus Ferdinandus Oviedus, in his book entitled The Summary or Abridgment of his General History of the West Indies, written to the Emperor Charles the Fifth (Holy Roman Empire, 1500 to 1558.) He said, and I easily believe it that the Bermudas were of greater diameter than they are now. “In the year 1515... I sailed above the Island Bermudas, being the farthest of all the islands that are yet found at this day in the world, and arriving there at the depth of eight yards of water, and distant from the land as far as the shot of a piece of ordnance, I determined to send some of the ship to land, as well to make search of such things as were there as also to leave in the island certain hogs for increase. But the time not serving my purpose by reason of contrary wind, I could bring my ships no nearer‑the island being twelve leagues in length and sixteen in breadth, and about thirty in circuit, lying in the thirty‑three degrees of the north side.” (30 miles in length, 40 in breadth, 75 miles circumference)

True it is the main island may be some sixteen miles in length and liesin a direction east‑northeast and west‑southwest, the longest part of it, standing in thirty‑two degrees. There is a great bay on the north side in the northwest end, and many broken islands in that bay, or and a little round island at the southwest end. As occasions arose, we gave titles and names to certain places.

These islands are often afflicted with storms with great strokes of thunder, lightning, and extremely heavy rain. These storms are so violent that it may well be that they have torn down the rocks and thrown whole quarters of islands in the main sea some six or seven leagues and in time swallowed them all. Even at a great distance from the shore there is no small danger of these rocks as well the continually raging storms. Once I saw the mightiest blast of lightening and most terrible rap of thunder that ever astonished mortal men.

However, in August and September and even until the end of October we had very hot and pleasant weather. There was an occasional thunder, lightening and scattering showers of rain which passed swiftly over, but yet it would fall with such force and darkness that for a brief time we thought it would never be clear again.

In the beginning of December we had great hail storm, the sharp winds blowing northerly, but it continued not. And to say truth, those north and northwest winds blow whether it is wintry or summer weather. We had much taste of this kind of winter, for those cold winds would suddenly alter the air. But when there was no breath of cold wind to bring the moist air out of the seas from the north and northwest, we were rather weary of the heat rather than pinched with extremity of cold. Yet the three winter months‑December, January, and February‑the coldwinds blew, and indeed then it was heavy and melancholy there.

The winds were not as rough in March as they were in winter. Yet even in the cold of winter the birds would breed. I think they bred there most months in the year. I myself saw young birds in September and at Christmas and even in February when the mornings are fresh and sharp, like they are in England in the month of May.

The soil of the whole island is one and the same: dark, red, sandy, and dry. I believe the soil would be incapable of growing our familiar commodities or fruits. Sir George Somers, in the beginning of August, planted a garden in Gates Bay (where the govenor first leapt to shore). He sowed muskmelons, peas, onions, radish, lettuce, and many English seeds and kitchen herbs, all which grew enough to be seen above ground in only ten days. In spite of sprouting so early, these plants came to no proof and did not thrive. We never knew for sure if they were hindered by the vice of the soil or whether the plants were destroyed by any of the numerous types of small birds or by flies. I never saw any worms nor any venomous thing like a toad or snake or any creeping hurtful beast. There were only some spiders which, as many people agree, are signs of a great store of gold. But they were long and slender‑legged spiders, and whether venomous or no I know not. I believe not since we often found them in our linen, in our chests and drinking cans; but we never received any danger from them. A kind of black beetle there was which gave an odor like many sweet and strong gums mixed together whenever it was hurt.

Plant Life on Bermuda

There are thickets of good cedar trees, fairer than those in Virginia. It has berries that we boiled, strained, and let stand for three or four days which made a pleasant drink. These berries are the size and color of currants, full of little stones.There is also a great store of palm trees with a kind of simeron - or wild palms which resemble true palms in growth, fashion, leaves, and branches. The tree is high and straight, sappy and soft - too soft for any use. There are no branches except in the uppermost part. In the inmost part of the head is a fruit they call palmetto and it is the heart and pith of the same trunk. It will peel off into smooth, delicate, satin white pleats. You may write on these pleats like a paper. The leaves are broad and a man may put his whole body under one of them during rain because they are stiff and smooth. With these leaves we thatched the roofs of our cabins, and roasted the palmetto which tasted like fried melons. They bear a black, round berry which were ripe and luscious in December. The leaves are shed in December and burgeon fresh and tender in March.

Besides the cedar trees and palmetto palms, there are other kinds of tall and sweet smelling woods of diverse colors, including black yellow and red. One bears a round, blue berry that was often eaten by our people.Other kinds of high and sweet‑smelling woods there be, and divers colors: black, yellow, and red, and one which bears a round blue berry, much eaten by our own people, of a stringent quality and rough taste on the tongue. This would stop the diarrhea that was caused by eating the luscious palm berry, for the nature of sweet things is to cleanse and dissolve.

We found a kind of pea growing upon the rocks, the size and shape of a pear which was full of sharp, prickly thistles so we called it “the prickle pear.” The outside was green but when opened it was a deep purple color, full of juice like a mulberry and tasted similar. We ate these prickle pears both raw and baked.

No rivers nor running springs of fresh water could be found. When we first came, we dug and found soft bubbling of water. Nevertheless the water soon sank into the earth and vanished. We dug wells that might fill with rain water.

Animals Found on Bermuda

The shore and bays round us, when we first landed first, provided a great store of diverse types of good fish. But it seemed that our fires we made on the shore, drove. But we made a flat bottom gondola from cedar with which we put off farther into the sea, and then daily hooked a great store of many fish including excellent angelfish, salmon, peal, bonitos, stingray, cavally, snappers, hogfish, sharks, dogfish, pilchards, mullets, and rockfish. Governor Gates dried and salted and, barreled them up so when we finally left we sailed out to sea with five hundred. For he had procured salt to be made with some brine (sea water mixed with rain water). He kept three or four pots boiling, and two or three men attending nothing else in an house close to his bay, set up for the purpose of making salt.Likewise in Furbusher’s Building Bay we had a large fishing net, which our governor had made of the deer traps which we were taking to Virginia. These nets were made by drawing the masts more straight and narrow with rope yarn, and which reached from one side of the dock to the other. I will boldly say we took five thousand of small and great fish at one catch, of pilchards, breams, mullets, rockfish and other kinds for which we have no names. We also found an abundance of crayfish, crabs, whelks and lobster larger than our best English lobsters under broken rocks. True it is that we found schools of fish in abundance in every cove and creek, I think, no island in the world may have greater store or better fish. For they, drinking the very water which descended from the high hills and mingled with juice of the palms, cedars, and other sweet woods grew fat and wholesome. Likewise herbs, roots and weeds grew sweet about the banks. So much better are those fish than the gross, slimy, and corrupt fish which feed in fens, marshes, ditches, muddy pools, where much filth is daily cast forth near the rivers of London.

We never saw unscaled fishes like eels or lampreys. Nor did we find any and such feculent and dangerous snakes.

I should refrain from telling about the types of whales we saw from shore. Sometimes a swordfish or thresher shark would prick the whale in the belly and he would sink and fall into the sea. Then he thrashed upward from his wounds with the thresher-shark beating him with his large fins flailing above the water. This is an example how those in the sea live in the same peril of mortal men on land where there is no certain security for those of high estate or low.

A great store of fowl is about the island, small birds, sparrows fat and plump like a bunting, robins of diverse colors of green and yellow, all became familiar in our cabins. There were others which were less common: white and gray herons, bitterns, teal, snites, crows, and hawks. In March we found hawks, tercels, oxenbirds, cormorants, baldcoots, moorhens, owls, and bats in great store. And upon New Year’s Day in the morning, our governor while walking with another gentleman, Master James Swift, killed a wild swan in a pond on our island.

A kind of web-footed fowl there is, which we did not see all summer and in the dark nights of November and December they would come forth, for they only feed at night. They did not fly far from home, and hovering in the air and over the sea, made a strange hollow and harsh howling. Their color is like rust, with white bellies. These gather themselves together and breed in the higher which are alone into the sea that the wild hogs cannot swim over to them. There in the ground they have their burrows, like rabbits.

I myself have been at hunting parties where we have taken three hundred of these birds in an hour to load in our boats. Our men found a pretty way to take them, which was by standing on the rocks or sands by the seaside, and whooping and yelling the strangest outcry that possibly they could. Their noise caused the birds to come flocking to that place, and settle upon the arms and heads of those who cried out, all the while answering the noise themselves. Our men grabbed them with their hands, but only kept those which weighed heaviest and let the others go. Our men would take twenty dozen in two hours of the biggest of them; and they were a good and well‑relished fowl, fat and full as a partridge. In January we had great store of their eggs, which are as large as an hen’s egg, white‑shelled, and have no difference in yolk nor white from an hen’s egg. There are thousands of these birds, and two or three islands were full of their burrows. At any time in two hours’ we could send over a boat and bring home as many as would serve our whole company. These birds see weakly in the daytime, and because of their cry and hooting, we called them “sea owls.” They will bite cruelly with their crooked bills.

We learned quickly that there were wild hogs upon the island. We brought our own swine ashore that had been saved in the wreck. After they had strayed into the woods, a huge wild boar followed them to our campsite at night. One of Sir George Somer’s men captured the wild hogs in a most unusual way. He lay quietly among our own swine, and when the wild boar came to the sows, he gently touched it and rubbed its side. He continued laying still while allowed him to fasten a rope with a sliding know to the hind leg. He caught two or three more after this.

Sometimes our hunters would bring home alive thirty or even fifty of these wild hogs in a week. Our dog held onto them while the hunters came. There are thousands of these on the islands and from August to November they were well fed with berried that dropped from the trees. We made pig stys for them at our campsite. We gathered berries for them to eat twice a day which kept them healthy and gave us a good supply of meat. Then when it was too windy to fish on the ocean we could kill some hogs. But unfortunately, in February, when there were few berries left on the trees, the hogs grew sickly. But even at that time of the year, the tortoises came in giving us plenty of food as we baked and roasted them.

The tortoise provided reasonable wholesome meat and our company liked them very well. And one tortoise would go further than three hogs. One of these turtles would provide 12 meals for six people. You cannot call their flesh either fish or meat exactly, since they lived most of the time in the water and fed upon sea grass. They would come ashore, make a deep pit on the sand where they laid their eggs and covered them, leaving them to hatch in the sun. We found five hundred of these eggs in one female turtle. Their eggs are as big as geese eggs.

Chapter Two

Ravens Sails with the Longboat

After our landing, we settled into our campsite as comfortably as could be expected in a place chosen to supply as much of needs as possible. Not long afterwards, we modified our longboat into a pinnace, as I am sure Your Ladyship has heard. (A pinnace is a light weight sailing vessel, larger than our longboat but smaller than most sailing ships.) We used the hatches of our ruined ship to build a deck so that no water would go into her, we gave her sails and oars. We pleaded with our master’s mate, Henry Ravens, a good navigator, to sail to Virginia with the message that we were about one hundred and forty leagues away and thirty-seven degrees.On Monday, August 28, Henry Ravens and our cape merchant, Thomas Whittingham, and six other sailors headed out from Gates Bay. To our surprise, they returned back to us Wednesday night, having attempted to leave the island from the north-northeast and sailing to the southwest. But they were not ableto due to the shoals and breaches. On Friday, September 1, they left the same route we came in, on the south-southeast of the islands. Ravens promised that if he lived and made it to Virginia, he would return to us by the next new moon with the pinnace that belonged to the colony (and had been towed by one of the other ships.)

Our governor gave instructions that fires be prepared on the islands to serve as beacons. But two months were wasted with men continually watching and feeding the fires on the promontory, looking longingly at the horizon for a rescue ship. But whichever way we turned our eyes, there was only air and sea.

The Building of A Pinnace and a Controversy

In the meantime, an experienced shipwright named Frubbusher in our company, began to build a pinnace. This Frubbusher was born in Gravesend, England but as an adult lived at Lime House and was a skillful workman. To help with his work of building this pinnace, our governor himself as well as a parcel of less qualified people, cut down, carried, and sawed cedar wood. The example of our governor to apply himself to any labor, regardless of how low or physical it might be, at length made the people more diligent and willing to work. We observed how example prevails above precepts, and how men are more ready to be led by eyes than ears.It sure was happy for us, who had fallen into the bottom of this misery to be shipwrecked, that we had such a governor with us, one who was so solicitous and careful, whose example and authority shamed our people and commanded them to work. Otherwise, I am persuaded, we all would have finished our days there on the island without hope of rescue, because the majority of the common people were willing to settle into a permanent home there on the islands when they found so plentiful of food. Perhaps even some of the better sort (higher class) of people would also have preferred to stay there.

Lo, what are our affections and passions if not rightly squared? Some dangerous and secret discontents nourished amongst us eventually led to such mischief and blood shed. Such discontent began first in the seamen, who in time had fastened onto the idea of staying on the island. Likewise, many of our landmen came to agree, and because a few of them were respected for their religious position the idea spread. Here is the angle by which they chiefly hooked others into their disquieted pool: that in Virginia they could expect nothing but wretchedness and labor, and may wants. Virginia did not have the fish, flesh, nor fowl which we found here in Bermuda. Ease and pleasure could be enjoyed in Bermuda, and since in either Virginia or Bermuda they were, for the most part, to lose the benefits both of their friends and country, it was as good or even better to stay and repose here where they should at least not have the hunger and wants of Virginia. (Editors note: The sailors who had been in Viriginia on previous expeditions could now share with the settlers, for the first time, the conditions they had seen themselves.)

Thus this was preached and published within the company by some who had never been particularly inclined to go to Virginia in the first place. And what has more power to attract the idle than liberty from work and promise of food and ease? So began such a murmur of discontent and disagreement of hearts and hands from the labor of building the ship which would redeem us from here, as each wrestled with his mate how to divorce him from his plans.

September Conspiracy

On September 1st, a conspiracy was discovered. Six principal instigators had promised to each other not to set their hands to any work or endeavor which might help build this pinnace. And each of these had independently tried to get the smith and one of our carpenters named Nicholas Bennit to join their group. These mutinous and dissembling imposters even used the profession of Scripture to recruit the smith and carpenter to join them. Their captain and one of their chief persuaders afterwards broke from the society of our company and like outlaws they retired into the woods, making a settlement and habitation of their own party. They chose to leave our quarters and live on another island by themselves. Happily, their plot was discovered, and they were condemned to the same punishment that they had chosen - but without smith or carpenter. Therefore they were carried to an island distant from us, and there they were left.The names of these individuals were John Want, their leader, a man from the county of Essex, who lived near the town of Saffron Walden. This seditious man was suspected by our minister of being a Brownist, (a religious Separatist who wanted to separate from the Church of England.) His confederates were Christopher Carter, Francis Pearepoint, William Brian, William Martin, and Richard Knowles.

But soon these six men missed the comfort of our company. Besides, they found their own society weary, if not loathesome for the offense they had committed to our group, at the very least a sorrow that their own number was not larger. Therefore they sent many humble petitions to Governor Gates, full of sorrow and repentence and earnest vows to redeem their former trespass and gave examples of the duties to the common cause and general business that they would perform. Our governor was quick to allow them back into our company since they appeared shamed and contrite.

January Mutiny by Stephen Hopkins

One might expect this incident could have been a warning to others who began to shake the foundation of our company’s quiet safety in a more subtle way. The first action was commenced by Stephen Hopkins, a fellow who had much knowledge in the Scriptures and whom our minister therefore chose to be his clerk to read the Psalms and chapters on Sunday when we assembled as a congregation. On January 24, 1610, he broke with Samuel Sharpe and Humfrey Reede who reported his actions to the governor. Hopkins falsely quoted the Scriptures with substantial arguments both civil and religious, stating that it was no breach of honesty, conscience, or religion to decline to obey the govenor or be led by his authority, unless it pleased them to do so, because the govenor’s authority ceased when our ship wrecked. Therefore they were freed from the authority of any man, and all were bound to provide only for himself and his own family. There were, Stephens argued, two apparent reasons to stay in this place: first there was an abundance of God’s providence in all manner of good food. Second, many hoped in reasonable time, if they grew weary of this place, to build a small bark with the skill and help of the aforesaid Nicholas Bennit. At this time Bennit was absent from our company and was now working on the main island with Sir George Somers upon his pinnace; but they insinuated that he was among the conspirators but with his help they might leave the island at their own pleasure. On the other hand, if they went to Virginia, the food supply would most assuredly be lacking, and it was also quite possible that they would be forced to remain in that country by the authority of the (Jamestown) commander and serve with their labor the desires of the adventurers there.When this information was laid out by these two accusers against Stephen Hopkins, the governor decided to let this offense have a public affront and hearing by these two witnesses before the whole company, without knowing what further arguments or other conspirators might be involved. At the tolling of a bell, all assembled before a corps du guard (a body of soldiers who took turns being on guard), and the prisoner was brought forth in manacles. He was accused and allowed to make a defense, but his answer was only full of sorrow and tears, pleading simplicity (little education) and denial. He was judged to be both the captain and follower of this mutiny and held worth y to satisfy the punishment of his offense with the sacrifice of his life. Our governor passed the sentence of a court martial upon him which belongs to those guilty of mutiny and rebellion. But so penitent he was, and made so much moan, describing the ruin of his wife and children (who were still in England) because of his tresspass. His pleas touched the heart of the better sort of the company, who therefore went with humble entreaties and supplications to our governor. Likewise, both Captain Newport and myself plead with Governor Gates, and we never left him until he had pardoned Hopkins.

Conspiracy & Danger Spreads

In these dangers and devilish disquiets, while the Almighty God sent us a miraculous delivery from the calamities of the sea and all blessings upon the shore, we should have been content and bound to one another in gratefulness. Instead we raged among ourselves to the destruction each of other. And what mischief and misery we would have suffered had we not a governor with the authority to suppressed the division. Yet was there a worse practice, faction, and conjuration afoot, deadly and bloody. In this new threat the life of our governor and many others were threatened, and such threats would have been successful if he had fallen. But such is the will of God who breaks the firebrands upon the head of him who first kindles them!Some thought that our governor had neither the authority nor the will to execute justice upon anyone no matter how treacherous or impious their crime, deceiving themselves regarding the unlawfulness of their acts. They went so far as to say that if they should be apprehended, they would happily suffer as martyrs. They drew a number of people into the plan to abandon our governor and to continue inhabiting this island. They then planned to make a surprise attack on our storehouse and by force to take food, cloth, cables, arms, sails, oars and whatever we had recovered from our wrecked ship. These were items preserved for our general use for our relief while we were on the island, and which we planned to carry with us when our pinnace was finished.

Giddy and lawless attempts always have something of imperfection. Actions of disobedience and actions of rebellion are both full of fear, not to mention ignorance of the devisers themselves. Some of the members of their association were not as strongly fortified in their conceits and broke from them. And before the time was ripe for the execution of their plan, the whole business was discovered as well as every agent and actor. They were not suddenly apprehended at once because the confederates were divided, living in separate camps: some were with us in the main camp, and the majority of the conspirators were with Sir George Somers on his island. Indeed, his entire company of sailors were involved. (Note the sailors followed the Admiral Somers while the passengers/settlers remained with Governor Gates. It’s interesting that we don’t know exactly where Captain Newport was - but I’m guessing he was with the governor??) From that point, every man was commanded to wear his weapon. Before that we had all walked freely from quarter to quarter and conversed among ourselves. But now every man was advised to stand upon his guard, his own life in danger while his neighbor was not to be trusted.

March: Nighttime Theft & Death of Henry Paine

The sentinels and nightguards were doubled. The passages of both the quarters were carefully observed. So nothing was attempted until a gentleman among them, one Henry Paine who was full of mischeif and every hour prepared something, decided to make good his own bad end when he was on nightwatch. It was on March 13, 1610 he stole swords, adzes, axes, hatchets, saws, augers, planes, mallets, etc. He was called out by the captain of that nightguard, and not only did Henry Paine give his commander evil language but he struck him with double blows. When he was not allowed to finish the watch, he went off duty, scoffing at the double diligence and attendance of the watch appointed by the govenor for this very purpose. The guard told him that if Governor Gates heard of his insolence he would be blamed and his life not worth very much. Paine replied with a settled and bitter violence in such irreverent terms that would offend the reader if I wrote his exact words. But the content of his speech was that the governor had no authority over anyone in this low-down colony and therefore the governor could kiss (etc.) The next day his words, including those additions that I have omitted here, were repeated in every public conversation, and at length were delivered to the governor. Governor Gates examined the transgression, all the more odious since it was done at such a dangerous time by a confederate. Considering the success of the transgression and the possible longterm outcome of such a notorious and bold impudency, the governor called Paine and the whole company before him. He was soon convinced both by the witness of the commander of the nightwatch as well as many others who were also on that watch. Our governor now had the eyes of the whole company fixed upon him. He condemned Paine to be instantly hanged. The ladder was readied, and after Pain had made many confessions he earnestly desired, since he was a gentleman, that he might be shot to death rather than hanged. Towards the evening, he had his desire, the sun and his life setting together.Sailors Take to the Woods: Somers Intervenes

Perhaps it was merely rage. Perhaps it was greediness after some little pearl that they thought should forever enrich themselves in this place. Perhaps it was a desire to forever inhabit this island. Or perhaps some other secret motivated them. But they sent an audacious and formal petition to our governor, subscribed with all their names and seals, and pleaded with him that they might not only stay here but also asked that he would perform other conditions that they asked. Namely, he should keep a previous promise to provide each with two suits of clothes and contribute food enough for one year - at the provision of one and a half pounds a week whhich had been all of our portion for the last nine months. (Note: Perhaps the greatest motiviation of these sailors to stay behind was the fact that they faced execution in England if they were charged with mutiny.)Our governor answered this petition by writing to Sir George Somers. Governor Gates stated that it was true that when they first arrived on this island, they had feared that they would not have the ability to make a vessel large enough to transport all the countrymen at once. Indeed, out of Christian compassion he mourned for his countrymen under his command that he foresaw they would have to leave behind on the island. His purpose was not to forsake them as savages, but to leave them all supplies fitting to defend them from want for a year or more. Because with the hazards of the sea any ships he would send to get them might be delayed. He reminded Sir George how he had asked him to remember the company that might be left on the island, so that by any means he could find them, either by his own means, by his authority in Virginia, or by the love and influence of friends in England he would rescue them sooner. It was never his intent to leave them abandoned and neglected without their redemption for any length of time. He then proceeded to ask Sir George Somers to tell them, that since now our own pinnace was being built that would be sufficient to transport the whole company, the previous charitable plans to provide for the company left on the island were no longer necessary. He asked him to advise the sailors that he could not grant their request. First, for His Majesty (King James) to decrease the number of his subjects sent to Virginia as planned, next to the adventurers currently in Virginia, and lastly what an imputation and infany it would be to their own reputations as admiral and governor since they had the authority to compel the resistant multitude to obedient and honest actions. For if they should not execute their authority correctly, the blame would not lie upon the people since commoners are often wavering and insolent. But the blame would be upon themselves, so weak and unworthy in their command. Moreover Gates entreated Sir George to apprehend them by any secret practice, since the obstinate multitude were no more to be agreed with than a murmuring and mutiny of rebellious and turbulent humorists who had not conscience nor knowledge to draw in the yoke of goodness. For in this business for which they had been sent out of England, and the expense of this enterprise that was committed to him, for the poorest of those in this group had cost the Company more than twenty pounds for his own personal transportation as well as the things that accompanied him. Therefore, he lovingly begged Sir George by the worthiness of his well-maintained good reputation, by the powers of his own judgement, and by the virtue of the ancient love and friendship which had these many years been settled between the two of them, to do his best to give this company in revolt these particular reasons why they should continue with the rest to Virginia. He asked him to work with them and by fair means reconcile those in mutiny and show them their errors. Then the governor would be ready to pardon them as he now did pity them, assuring them in general and in particular that whatever they had sinisterly committed or practiced previously against the laws of duty and honesty, should not be imputed against them. (In other words, they were not going to be charged with mutiny if they would come back now.) Sir George Somers did such a noble work and heartily labored as our governor asked, and he brought most of them back into our company. Indeed all returned except Christopher Carter and Robert Waters. These two would by no means come among Sir George’s men, hearing that Sir George had commanded his men indeed to surprise by force or any other means, since they refused to be entreated by more fair means. After that, these two were so wary to come near any of us and when we left the island we were willing to leave them behind. For that Robert Waters was a sailor who, shortly after we first landed upon the island, as you shall shortly hear, killed another fellow sailor of his. So when we sailed away, we left the murdered and the murderer dwelling together.

Services Held

During our time upon these islands, we had two sermons preached every Sunday by our minister. Every morning and every evening at the ringing of a bell we all gathered for public prayer. At these times the names of our whole company were called, and any who were missing were duly punished.For the most part our preacher’s sermons were on thankfulness and unity.

It pleased God to allows us to perform other Christian rites on this island. On November 26, 1609 one of the servants of Sir George Somers named Thomas Powell, who was his cook, married Elizabeth Persons, the maidservant of one Mistress Horton. There were also services on Christmas Eve and on the first of October.

Our minister preached a good sermon and afterwards he celebrated communion which included our governor and the greatest part of our company. On February 11, 1610 we had the christening of a daughter of John Rolfe and his wife. Captain Newport, myself,and Mistress Horton were witnesses, and she was named Bermuda.

Then again on March 25, 1610 we christened a boy who was born to the wife of Edward Easton the week before. Captain Newport, myself, and Master James Swift were godfathers, and this boy was named Bermudas. (Editor’s Note: Interesting the Wm Strachey was popular enough to be the godfather of both babies born on the island. It is also notable it was Christopher Newport, and not Somers or Gates who was named godfather of both babies.)

5 Deaths, Including 1 Murder

Likewise we buried five of our company: 1) Jeffery Briars, 2) Richard Lewis, 3) William Hitchman, 4) my god-daughter Bermuda Rolfe, 5) and one untimely Edward Samuell. This Edward Samuell was a sailor who was villainously killed by the aforesaid Robert Waters who was also a sailor. Robert Waters struck Edward Samuell with a shovel under the ear. He was apprehended and appointed to be hanged the next day since the event was done at twilight. Waters was bound fast to a tree all night with many ropes and a guard of five or six around him. His fellow sailors watched until the sentinels fell asleep. In spite of the justice showed to Samuel, a fellow sailor of their own crew, in spite of example not to fight and kill, and in spite of the unmanliness of the murder and horror of the sin, these disdained the justice, cut the bands that held Waters and took him into the woods. There they fed him every night. Later our governor reversed the verdict of the trial by the mediation of Sir George Somers upon many conditions. (Editor’s Note: Strachey does not include Namontack in the list of deaths. Namontack disappeared while out with the only other native, Machumps, who was suspected of murdering Namontack but it was never proved.)Building and Launching of Two Pinnaces

The Deliverance & The Patience

On August 28, 1609 (one month after the shipwreck) we laid the keel of our pinnace. On Februrary 26, 1610 we began to caulk. We had saved old cables which provided us with oakum to fill into the seams, and we also had saved a barrel of pitch and a barrel of tar which we used on the bilge (the seam of the bottom and sides of the ship.) We scraped clean the bottom with lime made from whelk shells and a hard white stone which we burned in a kiln then covered with fresh water and tortoise’s oil. On Friday, March 30, 1610 we towed her out in the morning spring tide from the wharf where she was built which opened into the northwest. This particular wharf could become violent, so therefore our governor had previously ordered a hundred load of stone be brought from the hills and laid about her ribs to break the violence of the flow. With much difficulty, diligence, and labor we saved her - all her bases, shores, and piles - which would have been lost on January 2, when her joints were not firm and a storm had hit that wharf.Therefore on March 30, we launched her without her rigging of ropes and sales to a little round island lying west-northwest and close aboard to the backside of our island. Here on this little island she was nearer the ponds and wells of some fresh water. From here we could also make our way to the sea easier since the channel there was deep enough to allow her to sail forth when her masts, sails, and all her trim should be about her. She was forty feet front to back by the keel and nineteen feet broad at the beam. Her floor was six feet high; her forward rake - or angle of the ship’s mast - was fourteen foot toward the front; and her rake aft (towards the back) was twelve feet long, being three feet from the top of her post. She was eight foot deep under her beam and there was four and a half feet between her decks with a rising of half a foot more under her forecastle in order to scour the deck with small shot if at any time we should be boarded by the enemy. She had a drop of eighteen inches aft to make her steerage and her great cabin larger. Her steerage compartment for the common passengers was five feet long and six feet high and had a close‑gallery aft, with a window on each side and two right aft. Most of her timber was cedar, which we found to be bad for shipping because it is brittle. Her beams were all made from the oak of our ruined Sea Venture, and some planks in her bow were also of oak. The rest were cedarwood which we got on Bermuda. When she began to sail when she was first launched, our governor called her The Deliverance. She weighed about 80 tons. 80 tons.

Before we left our old quarters and sailed to the fresh water with our new pinnace, our governor set up a memorial in Sir George Somer’s garden. It was made in the figure of a cross from some of the timber of our ruined ship which was screwed into a mighty cedar tree which grew in the midst of his garden. The top branches of the cedar he had chopped off so the violent weather would have less effect.

In the middle of the cross, our governor fastened the picture of His Majesty, King James of England, in a piece of silver of twelve pence. On each side of the cross he had the following engraved in copper in Latin and English:

“In memory of our great deliverance, both from a mighty storm and leak, we have set up this to the honor of God. It is the spoil of an English ship of three hundred ton, called the Sea Venture, bound with seven ships more, from which the storm divided us, to Virginia, or Nova Britannia, in America. In it were two knights, Sir Thomas Gates, knight, governor of the English forces and colony there; and Sir George Somers, knight, admiral of the seas. Her captain was Christopher Newport; passengers and mariners she had beside (which came all safe to land) one hundred and fifty. We were forced to run her ashore, by reason of her leak, under a point that bore southeast from the northern point of the island, which we discovered first the eight and twentieth of July, 1609.”

At the end of April, Sir George Somers also launched the pinnace he had built at a separate bay on the main island, and brought her into the channel where our pinnace now was anchored. This pinnace was 29 feet long by the keel, and its beam was 15 and a half feet wide. The luff, or widest part of the bow, was fourteen feet and the transom, or flat part of the back of the boat, was nine feet across. She was eight feet deep and six feet beneath water. He named her The Patience.

Chapter Three

Departure from Bermuda

From this time we waited for a favorable westerly wind to carry us away. But the wind continued for a longer time than usual from the east and southeast, the direction we were headed into. Early on May 10, 1610, Sir George Somers and Captain Newport went off with their longboats and two canoes and they placed buoys to mark the channel which we planned to sail out of. This channel was no broader than three times the length of our pinnace with shoals (coral reef and shallow sand) on one side and rocks on the other side. About ten o’clock, the day being Thursday, we set sail with an easy gale from the south, and since no small wind blew, we wanted to tow the Pinnace with our longboat. Yet even then we were unable to sail through the bouys that had been set, and just when we came to them we struck a rock on the starboard side (right side of a ship) that was under one of the buoys. Had that not been a soft rock that the Pinnace broke into pieces, God knows we would likely enough had to return to the island after our ten months of careful planning and labor for even a longer time.But God was more than merciful to us. When she struck upon that rock we were all dismayed and our hearts failed. But the cockswain, a man named Walsingham who was in the longboat, acted with a quick spirit. (Editor's note: Words appear to be missing which described what Walsingham actually did.) So by God’s goodness we led the ship out at six and a half fathoms (approximately 39 feet deep) The wind served us easily all that day and the next, when - God be ever praised - to the immense joy of us all we got clear of those islands. After that we held to a south course for seven days. Sometimes we had a fair wind and sometimes there was little wind or contrary wind. Twice we lost Sir George Somers on his pinnace even though we had given him our main topsail and forecourse (lower sail) as well.

Arrival in Virginia

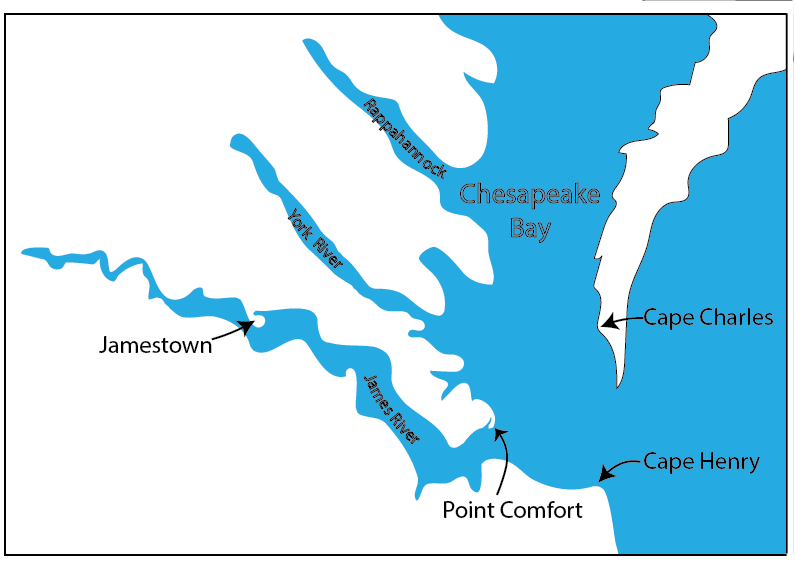

On May 17 we saw a change in the water with rubbish floating by the side of our ship, so we knew we were not far from land. About midnight on May 18 we sounded and found our ship was at thirty-seven fathoms. On May 19 in the morning we sounded again and found nineteen and a half fathoms with stony and sandy ground beneath us. On the twentith about midnight we noticed a sweet and marvelous smell from the shore, strong and pleasant which made us more than a little glad. In the morning at daybreak, as soon as one could see from the foretop of the ship, one of the sailors cried, “Land!” About an hour later, I went up and discovered two hummocks - or small mounds of land - to the south of us. North of those hummocks lay the land whose coast we would follow all the way to Cape Henry on the Chesapeake Bay. About seven o’clock that morning, we put out the anchor because the light wind was not strong enough to carry our ship against an ebb of water draining from a river into the ocean. We had planned to stay in place with our anchor cast until the next tide. But a strong wind came from the southwest about 11 am, so we set sail again, got over the bar, and headed for the cape.This is the famous Chesapeake Bay. Cape Henry, which is named in honor of our young Prince of England, is on the southern tip of the bay. Opposite Cape Henry and lying within the Chesapeake Bay is another headland that we named Cape Charles in honor of our princely Duke of York. Cape Henry and Cape Charles are about seven leagues from each other, with the Atlantic Sea running between them. Indeed, it is a goodly bay, and a fairer one is not easily to be found.

Those who talked to our men at the fort explained that all of the ships that had accompanied us last year had arrived in Jamestown - except for our Sea Venture with the fleet admiral as well as the small twenty-ton pinnace which was commanded by Michael Philes (Note: or Matthew Finch in other sources) which had been towed by the Sea Venture. We in turn told how our people who had been onboard the Sea Venture had survived. Only we could not learn anything of our longboat that had been sent from Bermuda and commanded by Ravens. Later we gathered from the Indians themselves, and especially from their chief Powhatan who told us that our men landed in a boat such as we described on one of his rivers. He described the people and made such scoffing sport that we gathered that it is most likely how the longboat arrived upon the coast, and not finding the James River, were at some time captured by the savages who had the military advantage and so their lives were cut off.

When our skiff returned from the fort to our pinnace anchored off shore, the good news of the arrival of our ships and men from last year made our govenor more than a little glad. He himself then went ashore, and soon, in contrast to all of our fair hopes that had been aroused by the news of the fleet’s arrival, had unexpected, uncomfortable and very heavy news of an even worse condition of our people in Jamestown.

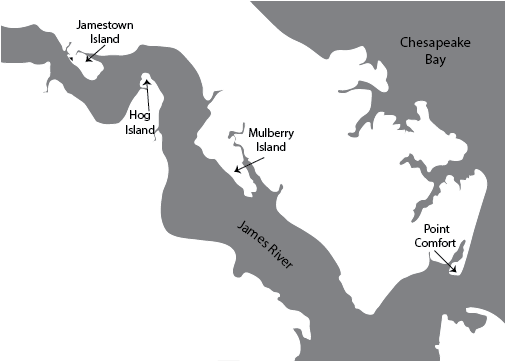

As you had already heard, the men at Jamestown had raised a fortification there upon Point Comfort last year. Since that time it has been perfected and has proved to be a strong fort under the command of Captain James Davies with forty men. It was given the name Fort Algernon by Captain George Percy, who we had just learned on our arrival was now president of the Jamestown colony, and we found that Captain Percy was likewise at the fort when we arrived. We got to Point Comfort about noon on Monday, May 21st. A mighty storm of thunder, lightning, and rain riding before an Indian town called Kecoughton, gave us a shrewd and fearful welcome.

For two days we plied sadly up the river with no wind stirring and only the help of the daily ocean tides. And on May 23, we cast our anchor before James Town where we landed. Our much grieved governor, first visiting the church in the fort, caused the bell to be rung. At that time all the people of Jamestown who were able came out of their houses to the church. There our minister, Master Bucke, made a zealous and sorrowful prayer, finding all things so contrary to our expectations, so full of misery and misgovernment. After the service, our governor had me read his commission as the appointed leader. Then Captain Percy, who had been president, delivered up to Governor Gates his commission, the old patent, and the council seal.

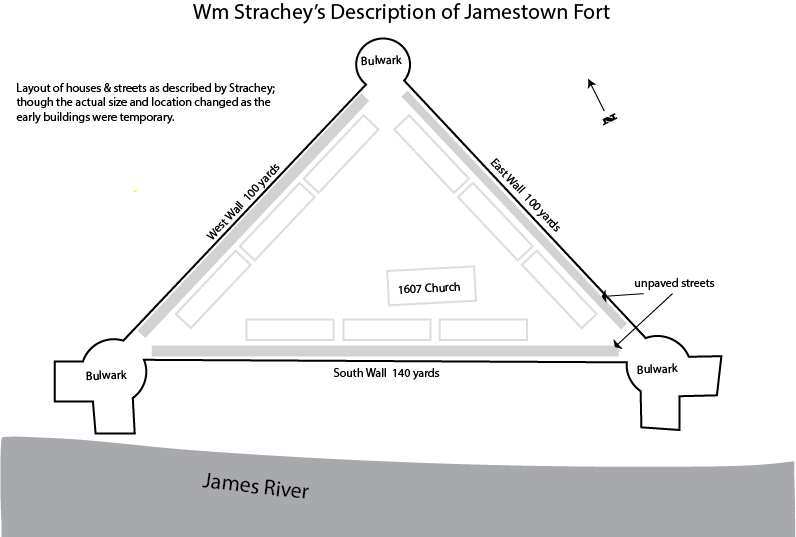

Condition In Jamestown

Viewing the fort, we found the palisade walls torn down, the ports open, the gates hanging off their hinges, and empty houses due to the owners’ deaths. Some houses were burnt because the dwellers would use the doors and houses rather than step into the woods a stone’s throw to fetch other firewood. And it is true the Indians killed as many men who stirred beyond the bounds of their blockhouse, as famine and pestilence did within the fort. with many more particularities of their sufferances brought upon them by their own disorders the last year than I have heart to express. So many particular sufferings befell them brought upon their own disorders in the last year than I have the heart to express here in this letter.In this desolation and misery our governor found the condition and state of the colony. And adding more to his grief, no hope how to amend it or save his own company and those yet remaining alive from falling into the same death. For we had brought from the Bermudas no greater store of provision than might well serve one hundred and fifty for a sea voyage; for when we left the islands we had no fear that such accidents possibly had befallen the Jamestown colony. Now it was not possible at this time of the year to amend the shortage of food by any help from the Indians. The Indians themselves at their best have little more than from hand to mouth, it was now likewise but their time to plant seed and all their corn had just been put into the ground. Those at the fort related to us that they had no means to fish; and yet, even if they had sufficient nets there were no sturgeon that had come into the river.

At that time, it pleased our governor to make a speech to the company, explaining that what provision he had brought from the Bermudas they should equally share with all. Andif he should find it impossible to supply them with food from this country by the endeavors of his able men who had just arrived with him, then he would transport them all back to England, accommodating them the best that he could on the vessels we had available. At this news there was a general acclamation and shout of joy on both sides, for even our own men who had just arrived began to be disheartened and faint when they saw this misery among those who had been living in Jamestown. For we were no less threatened with starvation than those we had just joined. In the meanwhile, our governor published certain orders and instructions, which he enjoined them strictly to observe, including the time that he should stay amongst them. These were written out and posted in the church for everyone to take notice of.

If I should be examined on how and why all these disasters and afflictions descended upon our people, I can only refer you, my Honored Lady, to the book which the adventurers have sent back to England, entitled “Advertisements unto the Colony in Virginia.” It describes the causes which produced such miserable effects. This includes the form of government, which turned out to be a mistake since it was not powerful enough among such a headstrong multitude. Particulary when you consider the supply last year of 1609, and that the leaders were on the Sea Venture and did not reach Virginia. But now they are in command here in Jamestown, which likely would have been more happily established had it pleased God to have them reach their desired harbor last year.(Editor’s Note: Strachey appears to be of the opinion that the Starving Time would not have happened under Gate’s leadership. Percy was not the best leader, but the colony was in a miserable place at a miserable time no matter who was leading.)

With the calamity of such a poor government, sloth, riot and vanity can occur in even the most settled and wealthy estate. Indeed, Right Noble Lady, no story can recall more woes and anguishes than these people thus governed have both suffered and pulled upon their own heads. And yet it is true some of them whose voices were not heard may easily be absolved from any guilt; while the divisive parties shall never be able to wipe away or cover their bad practices that has brought such discredit upon the country.

May I be pardoned for speaking freely to them. Consider what would happen if riot and laziness occurred in any of their best families in England with its abundance and plenty: continual wasting, no farming or planting, spending the store of provisions without ordering new provisions. What would befall the inhabitants, landlords, and tenants of that place other than hunger, famine, and death? Is this not the proverb of the wise man? “Yet a little sleep, a little slumber, and a little folding of the hands to sleep: So poverty comes as one that travels by the way, and need like an armed man.” And with this idleness, even the provisions that were in store were wasted to a great extent. And the headless multitude, many without good upbringing, education or religion, did not employ themselves in the tasks for which they were brought here. They were unwilling themselves to sow corn for their own bellies, to plant a root or herb for their own particular good in their gardens or elsewhere. With neglect on one hand and sensual over-indulgence on the other, all things were allowed to run on, to lie sick and languish. So how could it be expected that health, plenty, and all the goodness of a well‑ordered state would flow in this country?

Scarcity of Food

Since you have a right and noble heart, Worthy Lady; you be the judge of the truth. I beg you not to conclude that the wants and wretchedness which they have endured come out of the poverty of this country. Both the land or rivers have enough in their veins to convince them of such lies and excuses, and to prevent those common calamities. What England may boast of with its rich farmland, God and nature have favorably bestowed upon this country as well. The situation, height, and soil here in Virginia provide the same assurances of our own, well‑planted native country. Just as the soil of our own country might be improved and bring forth more food, so it is true in lands faraway. For we have seen with our own eyes, even though we are new to this land, that no country yields better corn. Not far from our fort we have large fields of such corn. Besides, we have many vines growing in a nearby woods which yield a plentiful crop of grapes. If these natural vines were planted and dressed by skillful wine-growers, would we not have perfect grapes and fruitful vintage in a short time?We have also tested some of our own English seeds, kitchen herbs, and roots, and find them to prosper as speedily here as they do in England.

Only let me truly acknowledge there are a hundred or two hundred hands, dropped here year after year, with poverty and leisure. They were ill-provided for before they came to this place and even more poorly governed once they got here. There are men of such distempered bodies and infected minds that no examples, either of goodness or punishment, can deter them from their habitual lack of duty or reverence, or terrify them enough to prevent a shameful death. This must be the carpenters and workmen in this so glorious an undertaking!

Then let no rumor of the poverty of this country change any man’s plan who has considered coming to this land. Such elemental seeds lay in the womb of this country which could produce many fair births of plenty and increase. There are no better hopes in any land under heaven to which the sun is no nearer a neighbor. I say again, let no false rumor by any person here or at home prevent any man’s fair purpose to come here or persuade them not to support this business. (Editor’s Note: Strachey sounds like he is writing on behalf of the Virginia Company and blaming the settlers for their fate.)

I will acknowledge, Dear Lady, I have seen many who do care about the unity and general endeavors. How contentedly do the laborers work when men of rank and quality assist and oversee their labors! I have seen it, and yet I protest it. I have heard the inferior people cheerfully profess that they should never refuse to do their best work when worthy and noble gentlemen go in and out before them. Not only that, but as the occasion should arise, they would defend them with their sword as well as help them with their hands. (Editor’s Note: Ranking by class at its best - or worse. Strachey would likely never have imagined how cringe-worthy his statements would be to men and women of a free society. No mention is made that it was the gentlmen, “men of rank,” that did so little to help the fort under John Smith.)

And it is to be understood that such laborers are not over-worked but easily finish their morning work by ten o’clock. Then they are allowed to use their time at their own pleasure until 3 o’clock. And then their day’s labor is finished at sunset If this business here shall continue, I believe with God’s favor we shall see a country fitted for trade that will most assuredly advance to the profit of both the adventurers here and the townsmen back home.

Desperate Need For Food

From May 23, when we arrived at Jamestown, until June 7th, our governor attempted to preserve this colony, using both his own judgment and the advice of Captain George Percy and those gentlemen of the council. But after much debate, it appeared that it would not be possible for the colony to survive, considering that the little food we which we brought from the Bermudas in our ships could only last about ten days, and then we would all face starvation.The Indians were poor with little food for themselves, and were forbidden by their subtle King Powhatan to trade with us at all. They were also ordered to attack any boat on the river or any of our people who left the fort. Not long before our arrival our people had a large boat attacked and many of our men killed even within the command of our blockhouse. Likewise they shot two of our people to death four or five days after we arrived. But even after these attacks, they would dare to enter our gates and trade with us. Indeed, they came as spies to discover how many had died and how many were left alive. Our governor saw their subtlety and would not continue with it. They were such hard traders and had such contempt for us, that they would give us only a small basket of corn for the same amount of copper that they had previously given a bushel.

It is the fault of the mariners that our colony suffered this problem, for in every voyage here the seamen have taken advantage of our needy people. The sailors would not give the people so much as a dust of corn nor a pint of beer or the least bit of comfort or relief unless they paid four to five times the rate of exchange. And that in spite of the fact that that beer had probably been stolen by them from some particular supply or from the general store. Such an uncharitable parcel of people they are. When the lord governor and captain general arrived with the fleet, I myself heard the master of the ship say he would not part with any of the goods he had brought to trade, not even a can of beer, unless he got an East Indian increase of four for one. Besides, to harm us even more, they would send off their longboats full of goods by night to neighboring Indian villages. And in spite of the laws of the fort which pronounced death for this trespass, they would trade with the Indians and give them such a large quantity of English copper for their trifles of otter skins, beavers, raccoon furs, bears skins, etc. Therefore, when the trade master of our colony would go to the Indians by day to offer copper in exchange for corn, the Indians would laugh and scorn their money, telling them what bargains they had got the night before from the men of our great ships. Thus, by exchanging valuable copper for these trifle skins, these dishonest sailors have been a consequent cause of the starvation of many worthy men in Jamestown this past year.

But I hope to see a true change and reformation of these shameless people as well as a change in the various intolerable abuses they have put on the Jamestown colony. There also needs to be a better plan for the transportation of provisions. Needed supplies should not be sent here under the charge of an assortment of money-makers with the result that only a fraction of supplies make it into the general store or to the parties to whom they were sent.

For the speedy correction of this serious problem, I understand the lord governor and captain general has requested to the council that the provisions should no longer be given to the care of the ships’ pursers (money officers). The council should send the provisions that are ordered. They should appoint a Commissary General of the food supply who will keep a careful account of the amounts of each product transported on every voyage, including the amounts of bread, meat, beer, wine etc that are received from the tradesmen in England. This Commissary General will deliver this list to the Master of every ship who will make sure he delivers everything on the list to the Treasurer of the store in Virginia. Otherwise, the ship Master will have to pay for the goods out of his own pocket. This will prevent the pursers, stewards, coopers, and quartermasters from giving themselves and their friends double allowances of supplies during the voyage, all the while thinking it is fine to steal from the Company and people.