Did Pocahontas Save John Smith?

Did Pocahontas actually rescue Captain John Smith from certain death? Read the historical records about John Smith and Pocahontas to compare history and legend.

This is part of the series: Historical Facts About Pocahontas. It may be helpful to review the the 18 documented incidents in the life of the real Pocahontas before reading this article.

Long before many individuals heard of Jamestown, let alone knew where or what it was, they were familiar with the dramatic story of young Pocahontas rescuing John Smith. It's an action-packed story of courage laced with romance. But...is it true?

Pocahontas and John Smith Controversy

This is one of the most disputed events in the narrative about Pocahontas. Our purpose here is to check the historical records and determine what is legend and what is history.Seven months after they first arrived in Jamestown (April 1607), Captain John Smith set out with 9 other settlers and two native guides to trade with the native tribes for food for the settlers in their fort. The colony only had enough food left for 14 days. Seven men were left guarding the barge of food and Smith and two others set out further with their guides. Suddenly they were attacked. Smith was captured; the other two were killed. Smith was then transported from eight or more villages over a period of several weeks until he met the great Chief Powhatan.

From "The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England,

and the Summer Isles

Author - John Smith: Published 1624

Date of Occurrence: approximately December 1607 - during John Smith's captivity by native tribesIn his 1624 history of Virginia he wrote:

two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on [Smith], dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beat out his brains, Pocahontas the King’s dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her armes, and laid her own upon his to save him from death, whereat the Emperour [Powhatan] was contented he should live to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper; for they thought him as well of all occupations as themselves.

There it is. The narrative as it stands in history. (There is one other quote from Smith about it, which is quoted below.)Why Is There A Controversy?

Over a hundred years ago a historian negative towards Smith questioned this account.Smith had written an earlier report in 1608 that had described his captivity. He said nothing about a rescue by Pocahontas. Later, after she had achieved fame, visited England, and died, he wrote his 1624 history with the statement above.

This is the primary source for the denial of its history.

There are other objectives to this account; as well as arguments in favor of it occurring.

Smith-bashing is a historical-cycle. There is no doubt he is a controversial character - then and now. Some of the men considered him a hero; others hated him - particularly the other leaders. That he ended up being a better leader didn't help their attitude. Jealousy seldom does.

Twice Captain Smith was sentenced to death while on the shores of the New World - and he was only here less than three years (April 1607 to October 1609). In fact, he was sentenced to execution on the very day he made it back to Jamestown after he was held hostage by the natives. The true historical narrative, in fact, is far more interesting as well as historically relevant than a question of who - if anyone - saved him from Powhatan.

Smith's 1616 Account of His Rescue by Pocahontas

From "Letter to Queen Anne"

Author - John Smith: Written 1616

Date of Occurrence: Same eventAlmost ten years later, Smith was living in England and Pocahontas had married a planter in Virginia. The Virginia Company brought Pocahontas to England and Smith wrote a letter to the Queen of England to request that she herself meet Pocahontas.

He wrote:

So it is, that some ten years ago being in Virginia, and taken prisoner by the power of Powhatan their chief King, I received from this great Salvage exceeding great courtesy, especially from his son Nantaquaus, the most manliest, comeliest, boldest spirit, I ever saw in a Savage, and his sister Pocahontas, the Kings most dear and well-beloved daughter, being but a child of twelve or thirteen years of age, whose compassionate pitiful heart, of my desperate estate, gave me much cause to respect her: I being the first Christian this proud King and his grim attendants ever saw: and thus enthralled in their barbarous power, I cannot say I felt the least occasion of want that was in the power of those my mortal foes to prevent, notwithstanding all their threats. After some six weeks fatting amongst those Salvage courtiers, at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine; and not only that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestown

Queen Anne never published the letter, and the original has not been found. Smith included the letter in his fourth book of the "Histories of Virginia" (1624.) Since both Pocahontas and Queen Anne were dead, might he have made up both the story of Pocahontas and his letter to the queen?Proof that Pocahontas DID Rescue Smith

What irrefutable evidence do we have that this account did, indeed, happen? NoneAll we have is John Smith's own report in that single sentence in 1624, as well as the paragraph in the letter to Queen Anne of England.

Verification by eye-witnesses? It isn't there.

However, and this is an important point, it would be impossible for there to be any eye witness accounts. He was the only Englishman there; the others were killed. All others present were illiterate.

So you can take John Smith at his word. Or not.

Proof that Pocahontas Did NOT Rescue Smith

What irrefutable evidence do we have that this account is false? NoneWe are faced with the same dilemma proving or disproving this account. All the players are dead, only one could write, and not everyone trusts his heroic accounts. Fair enough.

But you will find MANY statements across the internet declaring - as an absolute fact - that this rescue did not happen. What I find somewhat amusing, is that often those who declare "it could not have happened" go on to report what DID happen.

The facts, mind you, just the facts!

What they apparently don't realize is that most of those "facts" of "what really happened" are derived from Smith's 1624 History of Virginia. If you take away Smith's accounts and Strachey's accounts of Jamestown, we are left with a fraction of the material. This, of course, does not PROVE that Pocahontas rescued Smith, or that everything in his account is the gospel truth. Certainly there is no question that Smith is a biased reporter.

But there is also no irrefutable case that this did not happen.

Arguments Casting Doubt On Smith's Report

Here is where the rubber meets the road. For indeed there are reasons to question this account.- Why did Smith not write about it in 1608, and waited until 1624 after she was dead?

- Smith is stated to be a braggart who tried to make himself look good.

- Pocahontas was a child and would not have been present for an execution.

Although if you feel it is convincing, who am I to argue?

Arguments Supporting Pocahontas Rescue of Smith

While we have no irrefutable proof of this event, there is some internal evidence within Smith's writing to verify that his account does have historical validity.Smith tried to make himself look good?

What story would you concoct if you wanted to gain social status by your relationship with a popular person: that they rescued you OR that you rescued them?Using the argument that she was dead and couldn't refute his claims, Smith could have just as easily stated that HE had rescued HER. There would have been no one to refute his report that he saved her from drowning, or from her father, or from wild animals or anything else.

I mean this guy is the poster-child for toxic masculinity. Stating that a little girl rescued you does not exactly give you street cred.

In his 1624 history of Virginia, Smith reported his 1617 reunion with Pocahontas in England. She was the rising social star who impressed London. And she was ticked off with him and let him know it. The only one who exposed her ire towards him was Smith himself. Read the account of the stiff reunion of John Smith and Pocahontas.

Yes, Smith was defensive and liked to make himself look good. As the historian Edward Haile stated, "He writes like a man who has stood on the gallows twice."

Keep in mind what happened to those first leaders in Jamestown. Wingfield was tried, imprisoned, and deposed. Kendal was tried and executed. Ratcliff was deposed only to return and be tortured to death. Smith, who twice was sentenced to death by Jamestown leaders became the president, and was later violently opposed and sent home after a questionable accident and was expected to die.

Having survived, Smith faced censor from the Virginia Company for making the aristocrats do physical labor. (Really!) The initial leaders of Jamestown like Smith, Archer, Percy, Ratcliff, Wingfield all wrote defensive accounts of their leadership: trying to make themselves look good and the others (often Smith) look bad. They still got a bad rap - from the Virginia Company officers, each other, and history.

Let's just say being the president of James Fort was not a good move for those wishing to climb the proverbial career ladder. If ever nominated for such a position you would be wise to pass. And all of them sounded defensive in their reports.

Yes, Smith tried to make himself look good. Read the memoires of almost anybody and you will find the same. But his glowing report of his own leadership does not necessarily mean he falsified the account of Pocahontas. He faced no threat of execution because of her. If he wanted to lie simply to impress us, there were far better lies he could have told.

The Real Story of Pocahontas Supports the Action

When reading the 18 facts about Pocahontas we find numerous accounts by multiple people that support her character as a brave, spunky, vivacious favored-daughter of the king, who showed some serious interest in the English newcomers.She was given credit for saving Smith several times, as well as saving another hostage Henry Spelman, and another settler Richard Wyffine (Fact #8.) She visited Jamestown many times, leaving a strong impression cartwheeling naked around the fort with the boys (Fact #7.) The surviving documents give evidence that she cared about both her father and Captain Smith, but she had no trouble standing up to them or defying them. She was indeed, a spunky little imp, as the name Pocahontas is translated (Fact #2.)

Children weren't allowed at executions? Would that have stopped her? (We also have the written record below of another child who witnessed five executions.)

None of this, or course, PROVES that she saved Smith from the clubs while his head was on the two stones.

But Ralph Hamor stated, "It chanced Powhatan's delight and darling, his daughter Pocahontas - whose fame hath even been spread in England by the title of "Nonparella of Virginia." It was John Smith who first called her "nonparella" in his original 1608 report. The entire historical documentation supports the view that she was a woman of high-breeding and daring spirit that had no equal in native or British circles.

The Silent Record

One of several tragedies in the Pocahontas story is that we have no writings that she left. Did she keep a diary or write letters? If she did, they are lost.She did learn to read, and one would suppose it likely she had some ability to put words on paper. How valuable it would be to have the thoughts of a woman whose remarkable strength and compassion has been reduced to a bedtime story and Disney cartoon.

In spite of the lack of her own written words, her spoken words recorded by others echo with the same strong spirit centuries later. They come across in these sentences:

- Were you not afraid to come into my father's country, and caused fear in him and all his people? And fear you here I should call you father? I tell you then I will

- All must die, it is enough that the child lives.

Another View of Pocahontas

While the historical record of Pocahontas left by early 17th century British writers supports the narrative of a young woman who would risk her own life to save others, in recent years another picture has emerged. A leader of the Mattaponi tribe, Dr. Linwood Custalow, has published an account based on oral tradition that differs signficantly. Custalow states Pocahontas never defied her father, but her actions were based on love for him and his people. He reports abuse during the year of her captivity, culminating in her having a child by Thomas Dale (the marshal who led Jamestown during that time) and not John Rolfe. She was depressed, confused, and taken to England where she was murdered. It certainly is a darker picture.The problem with oral legends is that we cannot assess who stated the facts, when, and how they were transmitted. Oral legends are subject to outside influence. As a widely known example, the tradition of Robin Hood has been highly influence by movies and novels. But at least with Robin Hood we have a seven-hundred-year written record that reveals the layers that have been added to the legend.

Such analysis is not possible with the sacred oral tradition in Custalow's account. The information is stated to be from Pocahontas' sister who did attend her and was part of her entourage in England. But Pocahontas and her sister are from a different village than the Mattaponi. Moreover, it is noted that this account largely refutes the English account point-by-point. Those records were sent to England and published, but not widely circuluated in print in America for almost 200 years. (1776 was the beginning of the United States, and 1826 the emergence of a national identity and desire to publish the early history.) Few, if any, of the natives would have been able to read those accounts even if they had circulated in the New World earlier. Understandably, people have questioned how the oral traditions of a neighboring tribe would reflect the written record point-by-point for hundreds of years.

The significance of Custalow's account is that it shows the events in the written history through the cultural lens of natives. Indeed, when a woman is taken captive into an almost all male enclave suspicion of abuse immediately arises. Their suspicion of murder when she died suddenly is valid. Though John Rolfe states in a letter written two months later (June 8, 1617) that not only was the little boy sick but "they who looked to him had need of nurses themselves." It sounds like a contagious disease, though that does not rule out the native report of a poisoning.

Custalow has stated that natives had previously considered Pocahontas to be a traitor to her people. Actions such as warning them of an attack and choosing to stay with the English have been interpreted as antagonistic to her own culture. Custalow's narrative rescues Pocahontas from the villainy of betraying her people. Unfortunately, most of her actions that earned her a place in history as a heroine are erased. Instead she has become a victim with no choice or voice.

While respecting the native view of her actions, the written document of early 1600's portrays a woman of amazing courage who saw beyond her years and her immediate surroundings. Today we do not view someone who moves to another country or marries someone from another culture as betraying their family. But both the natives and the English were highly punitive to their members who chose to live with the other side. Both executed their own people for choosing to live with the others unless they were sent. And both sides had members who crossed over in spite of it being forbidden. In fact, archaeology has demonstrated that more natives were cooking and working in the fort than was previously known. And the English record is filled with complaints of settlers who deserted - which meant they went to live with an Indian tribe. Today we don't see them as traitors; but then they did. Nor do we see it as a betrayal of family if someone embraces another religion.

We do see Pocahontas' affinity for her people in the written record in that she had natives around her in Virginia while married to Rolfe and while traveling to England. In her reunion with Smith in a social setting she rebuked him, supported her father and criticized the English.

Rather than being a token prize of a conquered people, as she has more recently been described for her London tour, she had long been reputed to be the nonparella - or person without equal. While the written record is being disputed, her acclaim from multiple sources does depict her heroism. Take that away and Pocahontas disappears. Being a victim would not cause her contemporaries to say, "She is without equal."

Spelman's Account

Spelman's intriguing account was discovered less than 200 years ago. The preface of the book stated it, "happily turned up in the late Dawson Turner's library of manuscripts, dispersed by auction in London by Misters Puttick and Simpson in 1859 being No 444 of the catalogue." And what a find! Here we have an eyewitness account of an English boy's life who lived two years with Powhatan and neighboring tribes.This account is captivating reading of its own account, but of particular interest to our topic in that it validates Smith's narrative of Pocahontas in several ways. He witnessed five executions during his time with the Indians.

From "Relation of Virginia"

Author - Henry Spelman: Published 1850

Date of Occurrence: 1609 to 1611Then those for murther were beaten with staves till their bones were broken, and being alive were flung into the fire. The other for robbing was knock'd on the head, and being dead his body was burnt.

His description of the manner of death correlates with both Smith's 1624 account of his rescue by Pocahontas as well as Percy's 1625 account of Ratcliffe's death. Indeed, the fact that he was a witness as an adolescent not much older than Pocahontas might confirm the possibility of her presence, even though more recently people have stated a child would not have been present.Spelman validates another confusing aspect of Smith's report. Spelman stated repeatedly that he was "well-used" though he was often afraid for his life. For the most part the "friendly-hostages" were treated well on both sides. Spelman is the only one that informs us that for a time he and two other English boys were together. Thomas Savage and the "Dutchman" named Samuel were held by the natives. At one time, the three of them chose to leave Powhatan to go with the chief of the Potomac tribe who treated them better:

"...showed such kindness to Savage, Samuell, and myself as we determined to go away with him....The Powatan presently sends after us, commanding our return, which we refusing still went on our way. And those that were sent went still on with us till one of them, finding opportunity, on a sunden struck Samuell with an ax and killed him; which I seeing ran away from the company, they after me, the king and his men after them."

Talk about action-packed drama!In another town he was beaten by two of the King of Pasptanse's wives:

she struck me 3 or 4 blows; but I being loith to bear too much, got to her and pull'd her down, giving her some blows again; which the other of the king's wives perceiving, they both fell on me beating me so I thought they had lam'd me.

Now that would have competed with YouTube's most-viewed fights. Then Spelman fled fearing retribution for injury to one of the women, but instead the chief:he sent me his young child to still, for none could quiet him so well as myself...He answered all was well and that I should go home with him, telling me he loved me and none should hurt me

So in the midst of watching executions, getting beaten, seeing his buddy killed, and acting as a translator, the kid is the chief's best babysitter.Spelman lived in fear, yet reported he was treated well which reflects the same sentiment Smith expressed to Queen Anne above that, "I cannot say I felt the least occasion of want that was in the power of those my mortal foes to prevent, notwithstanding all their threats."

Spelman lived two years with the natives and his account stands alone as an eye-witness of good and bad as an English boy living among natives. He writes as one who grew up in two worlds in contrast to the the more analytical assessment of native culture by William Strachey or Thomas Harriot or the six-week captivity of Smith.

Interestingly, Spelman never mentioned Pocahontas in his written account, even though Smith and the historian William Stith describe that Pocahontas saved his life and Argall reports he was present at the time of her abduction. Tradition has it his wife was a sister of Pocahontas. He doesn't mention her at all.

Possible Validation of Smith's 1608 Report

Let's re-examine one of the strongest arguments against Smith's narrative about his rescue by Pocohontas: he did not mention it in his 1608 report.It is a valid argument against his tale. But reading between the lines we find clues to something much more important than the famed story of Pocahontas, as well as a reason she was not included in his initial report.

John Smith's Captivity by Powhatan

From "True Relation of such Occurrences and Accidents of Note as hath hap'ned in Virginia"

Author - John Smith: Published 1608

Date of Occurrence: approximately Dec 160720 or 30 arrows were shot at me, but short. Three or four times I had discharged my pistole ere the King of Pamaunck, called Opeckankenough, with 200 men environed me,[or encircled] each drawing their bow.

At each place I expected when they would execute me, yet they used me with what kindness they could, approaching their town, which was within 6 miles where I was taken...All the women and children, being advertised of this accident, came forth to meet them, the king well-guarded with 20 bowmen, 5 flank and rear, and each flank before him a sword and a piece, and after him the like, then a bowman, then I, on each hand a bowmen, the rest in file in the rear

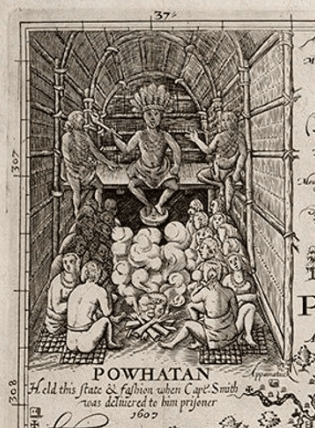

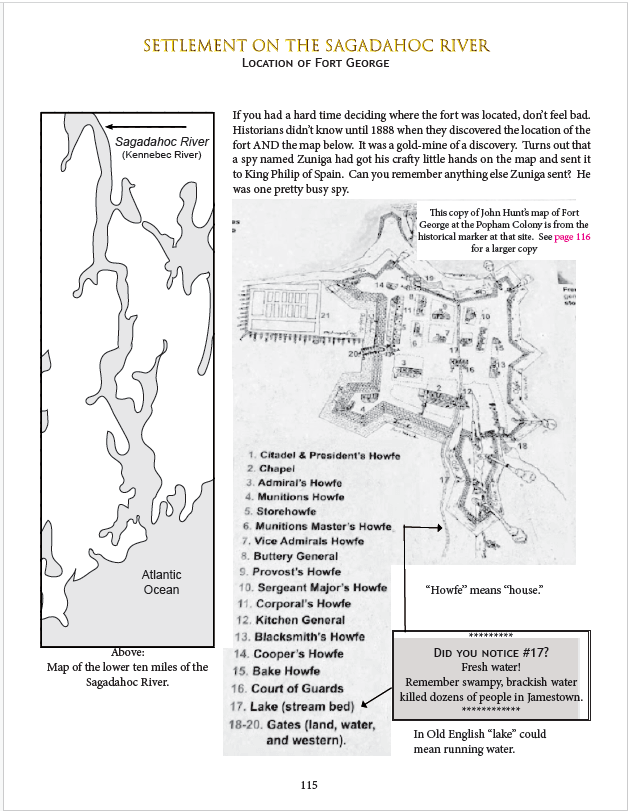

Smith records being taken to at least 8 different towns, before finally being led to Werowocomoco. It is notable that Pocahontas was from the village of Werowocomoco 12 miles north of Jamestown. Like other children of chieftains, she was raised in her mother's village. Chief Powhatan was at the village of Werowocomoco instead of his home village of Powhatan 35 to 40 miles west of Jamestown. Finding Chief Powhatan might have been the reason Smith was led from village to village.Arriving at Weawocomoco, their emperor proudly lying upon bedstead a foot high, upon ten or twelve mats, richly hung with many chains of great pearls about his neck, and covered with a great covering of rahaughcums; at his head sat a woman, at his feet another, on each side sitting upon a mat upon the ground were ranged his chief men on each side the fire, ten in a rank, and behind them as many young women, each a great chain of white beads over their shoulders, their heads painted in red, and with such a grave and majestical countenance as drave me into admiration to see such state in a naked savage.

This scene of Smith before Powhatan in 1607 is in the

upper left hand corner of his 1612 Map of Virginia

He kindly welcomed me with good words and great platters of sundry victuals, assuring me his friendship with my liberty within four days.

As with Spelman, we note kind words, plenty of food, contrasted with a fear of death as Smith and Powhatan are surrounded by bowmen (flank and rear.) Smith also addressed the fear of death and simultaneous good treatment with these curious words:Each morning, in the coldest frost, the principal to the number of twenty or thirty assembled themselves in a round circle a good distance from the town, where they told me they were consulted where to hunt the next day. So fat they fed me that I much doubted they intended to have sacrificed me to the quiyoughquosicke, which is a superior power they worship. A more uglier thing cannot be described. One they have for chief sacrifice.

We note that in this approximately 40 page report of 1608 - written within a few months of the event, sent to England, redacted and published by the end of the year - there is no mention of Pocahontas delivering him from the clubs. That incident was described above in the single sentence (albeit a run-on sentence) from his over-400-page 1624 History of Virginia written over several years in his leisure.- Approximately 90% of the 1608 "True Relation" is a report of the natives, the locations of their villages, and their interactions with them.

- 25% of the report is his captivity which probably shook him up more than he would want to admit.

- Powhatan dominates the discussion, understandably since he was a lord of over 30 villages and a powerful social and military leader.

- Powhatan - the chief, the village, the confederacy, and the river - also dominate the map Smith was already making.

- the English war with Spain

- Other tribes that had been hostile to the Jamestowners

- Tribes inland from the James River Falls

- "He described a country called Anone where they have abundance of brass and houses walled as ours"

- Described King James and Admiral Newport's military force on the seas which "he admired and not a little feared."

- An alliance between Powhatan's tribe and Smith's fort - "He desired me to forsake Paspaliegh and to live with him upon his river...to give me corn, venison, or what I wanted to feed us, hatchets and copper we should make him

Any direct threat of death from Powhatan or rescue by Pocahontas is not mentioned in the 1608 report. However, here are a few words in these quotes above from this 1608 "True Relations" that might support his later report:

- At each place I expected when they would execute me

- All the women and children, being advertised of this accident, came forth to meet them with Chief Powhatan and behind them as many young women, each a great chain of white beads over their shoulders

- I much doubted they intended to have sacrificed me

Also, the fact that he identified the location of his captivity as Pocahontas' village of Werowocomoco in his 1608 lends credibility. If he was making up a fictitious story in 1624 to impress others that a famous woman had saved him when she was a mere child, it was a mighty lucky thing for him that his previous account of the episode had taken place in her village.

The 1608 Report Was Edited

The publisher stated he excluded content that "I would not adventure to make public."The Virginia Company was notorious for censuring content that would discourage others from joining them. (No kidding, settlers even were threatened with the death penalty for speaking ill of the colony. Ultimately, that didn't stop the reports that came out anyway.)

Smith did not know when he set the letter back with Master Nelson aboard the Phoenix that someone would publish it by the end of the year, nor did he have any control over what was included or excluded. But there are multiple places where the text is cut short and it has obviously been edited for various reasons. All we have is the published version.

It may be possible that the story of Pocahontas was included in the original, but was one of the things edited out so new adventurers would not be discouraged from joining.

Brains getting smashed out? Being held a slave to make bells and beads for a girl? Yeah, I would say it might discourage a few folks from buying a ticket aboard the next ship.

What He DID Say About Pocohontas in 1608

What is highly relevant to our discussion, is what John Smith DID report to the Virginia Company that did make it into the published record. This was Fact #4 on the facts of Pocahontas, but it serves to document something else here.Powhatan, understanding that we detained certain savages, sent his daughter, a child of ten years old, which not only for feature, countenance, and proportion much exceedeth any of the rest of his people, but for wit and spirit the only nonpareil of his country. This he sent by his most trusty messenger, called Rawhunt, as much exceeding in deformity of person, but of a subtle wit and crafty understanding. He with a long circumstance told me how well Powhatan loved and respected me and, in that I should not doubt any way of his kindness, he had sent his child, which he most esteemed, to see me, and a deer and bread besides for a present, desiring me that the boy might come again, which he loved exceedingly. [The boy refers to the English child, Thomas Savage, who lived with the Powhatans for a time but their chief had recently sent back to Jamestown, and now requested his return.] His little daughter he had taught this lesson also... ...we guarded them as before to the church; and after prayer gave them to Pocahuntas, the king's daughter, in regard of her father's kindness in sending her. After having well fed them, as all the time of their imprisonment, we gave them their bows, arrows, or what else they had, and with much content sent them packing. Pocahuntas also we requited with such trifles as contented her to tell that we had used the Paspaheyans very kindly in so releasing them.

As far as we know, Powhatan never went to Jamestown. It appeared he made visiting dignitaries - both native and English - come to him. Perhaps that was a show of power; but could also be a smart safety precaution.This was the first recorded visit we have of Pocahontas coming to Jamestown from her village of Werowocomoco 12 miles away. She is reported to have been a frequent visitor later, but in this her first visit she comes in the care of Powhatan's trusty messenger Rawhunt.

Why would Powhatan send his daughter to ask for the release of hostages? Why not simply send Rawhunt?

Is it not possible that Pocahontas was sent because Smith owed her something? If she had saved his life, who better to come and request the release of their hostages?

Written Quickly, Then Dispatched

Another fact that might lend support to Smith's credibility is the timeline. He went out on his journey in November 1607 and made it back to Jamestown alive on January 12, 1608. Some of the Jamestown leaders blamed him for the death of his two comrades; some of his fellow colonists welcomed him with joy. But not all:Great blame and imputation was laid upon me by them for the loss of our two men which the Indians slew, insomuch that they purposed to depose me. [More than depose; we learn from others he was sentenced to death.] But in the midst of my miseries (understatement!) it pleased God to send Captain Nuport, who arriving there the same night so tripled our joy as for a while these plots against me were deferred.

This was the second time Christopher Newport saved Smith's neck from the rope. There is absolutely no question that Smith had a real knack for getting himself into trouble. I mean, the guy had been captured, sold into slavery, escaped, dueled three enemies and won, and then knighted for it long before he ever stepped on Virginia soil.Meanwhile, besides surviving his trial, John Smith has plenty of work cut out for him. With this first supply, joyously received, came food and new settlers who needed homes and immediate on the job-training. Smith was not yet president, but undoubtedly his place on the council gave him a major role in organizing these green settlers.

Then some of the newcomers accidentally burnt the fort down:

Within five or six days after the arrival the ship, by a mischance our fort was burned and the most of our apparel, lodging, and private provision. Many of our old men diseased and of our new for want of lodging perished.

Big help these guys were! So in addition to expanding the fort from a triangle to a five-sided structure, Smith has to get MORE food from the natives. He seems to be in charge of negotiations.Every one of them, calling me by my name, would not sell anything till I had first received their presents, and what they had that I liked they deferred to my discretion.

Yes, Smith was singing his own praise again. But then again, he was the best negotiator they had. They didn't starve until after he left.In addition to rebuilding the fort, restocking up on provisions, Smith took Captain Newport on a village-by-village tour and another wit-to-wit contest with the Great Powhatan.

Back to the fort, he has to write his approximately 146 paragraph report (with multiple run-on sentences) by hand - with a feather quill no less - to be taken back to England as the First Supply departed. In the last paragraphs he mentioned loading the ship with cedar wood to "freight home."

In other words, Captain Smith was finishing his report as the ship was getting ready to sail. He had minimal time to add human-interest stories.

But the ship carried more than the trunks of cedar trees. When the Virginia Company reads his explosive report about Powhatan, King James himself gets involved. It wouldn't be until October 1608 that the Second Supply sailed up the river with new ultimatums. And it wasn't Pocahontus they were worried about. Powhatan revealed information about the Lost Colonists of Roanoke and the king demanded action!

References

Below are the original resources. Most can be found online as well as purchased from a variety of publishers. (These are public domain; written long before copyright laws.)A single print source for these and other Jamestown documents is:

- Haile, Edward Wright, Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony (1998)

Online sources: links to online sources are included below. Like much of the internet, these are subject to change. These links are not live as broken links that are bad for our site. They can be copied and pasted and put in your search bar. Alternatively, copy and paste the title of the book.

Sources

Hamor: A True Discourse of the Present Estate of Virginiahttps://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A02606.0001.001?view=toc

Smith: True Relation of such Occurrences and Accidents of Note as hath hap'ned in Virginia (1607)

http://www.virtualjamestown.org/exist/cocoon/jamestown/fha/J1007

Smith: Letter to Queen Anne (1616)

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/pocohontas/pocahontas_smith_letter.cfm

Smith: Discovered & Discribed (Map 1612)

https://www.captainjohnsmith.org/1612-map-of-virginia

Smith: The General History of Virginia, New England, and Summer Islands (1624)

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/56347/56347-h/56347-h.htm

Spelman, Henry: Relation of Virginia.

In addition to Spelman's account, the forward "To the Reader" describes the manuscript's rediscovery and the story of his rescue as recorded by John Smith and later William Stith.

https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/aj/id/8665

Strachey: The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia: The 1st Book of the 1st Decade (1618)

https://archive.org/details/historietravail00majogoog

Get the Early Settlers Unit Study

Available in Paperback OR Printable Download

199 pages (Includes Student Pages, Teacher Key, Schedule, Maps, Activities, and More)

Print It Now

Student and Teacher's Material Included

$5.99 Download - 199 pages

![]()

Softcover Edition - Mailed to You

The same pages are in the softcover book and the printable file. Bound copy is great for repeat use or co-op leaders.

![]()

16.95 Soft Cover Manual

199 pages

Mailed to You

Early Settlers Pages

Check out our other pages for the Early Settlers Unit Study

Get the Lion To Guard Us Unit Study

Student Guide AND Teacher's Answer Key Included

$2.99 Download - 78 pages

![]()

Our pages for A Lion To Guard Us

Clyde Bulla's Historical Fiction of Jamestown & the Sea Venture

About Our Site

Hands-On Learning